First published on The New Stack

Don’t hold off fixing problems until they become too big and difficult to manage.

No one wants to fail at microservices. No one sets out to do that. But it’s easy to do given the difficulty of microservices and the surprising number of ways we can fail at it.

I’m normally an advocate for microservices, well at least where they are warranted and when implemented well. Usually I’m teaching cheaper, simpler and more effective ways to use microservices, but in this article I want to take a different tack. I’m going to describe the many ways that we can fail at microservices. Towards the end, we’ll look at what we can do to escape the hell we created (or maybe that we inherited).

The myriad of ways to fail at microservices

There are many ways to fail at development. The following list is compiled from actual experience in the field. These are all real examples from real production applications.

I’m going to relate all of these problems to microservices. But I’ll concede that many are just ordinary development problems that have been turned up to 11 by microservices. Let’s get into it.

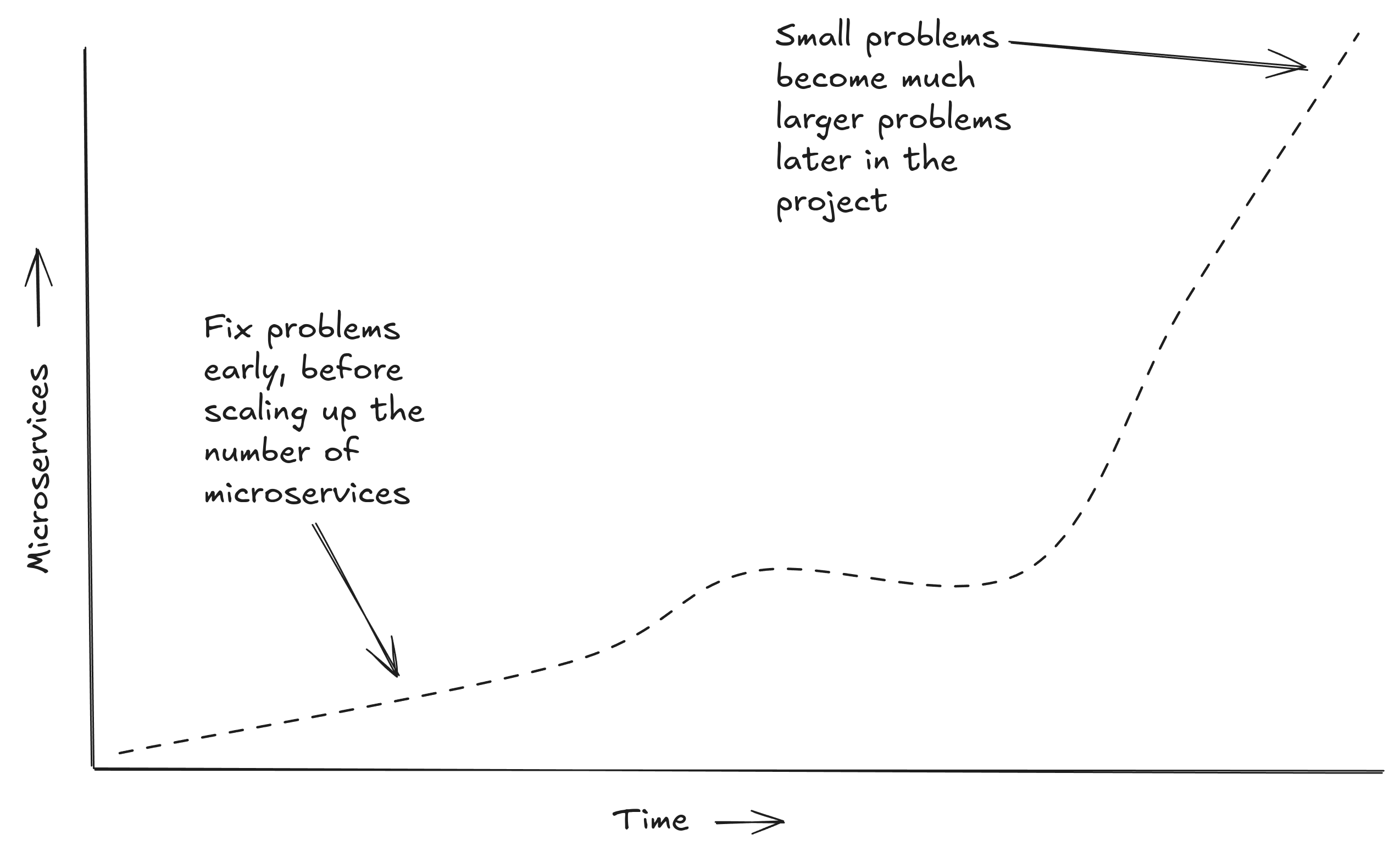

Hold off fixing problems

During development, especially when trying to move fast, you’ll be tempted to put off fixing non-essential problems until later.

The longer you wait to solve problems with infrastructure, automated deployments, automated testing, code reuse, etc, the more entrenched these problems become and the harder they will be to fix. As you scale up the number of microservices, any problems you have will also be scaled up.

Mounting problems can eventually outpace your team’s capacity to fix them. At this point you might complain about having an under-resourced team. If only you had addressed the most crucial problems before they spiraled out of control.

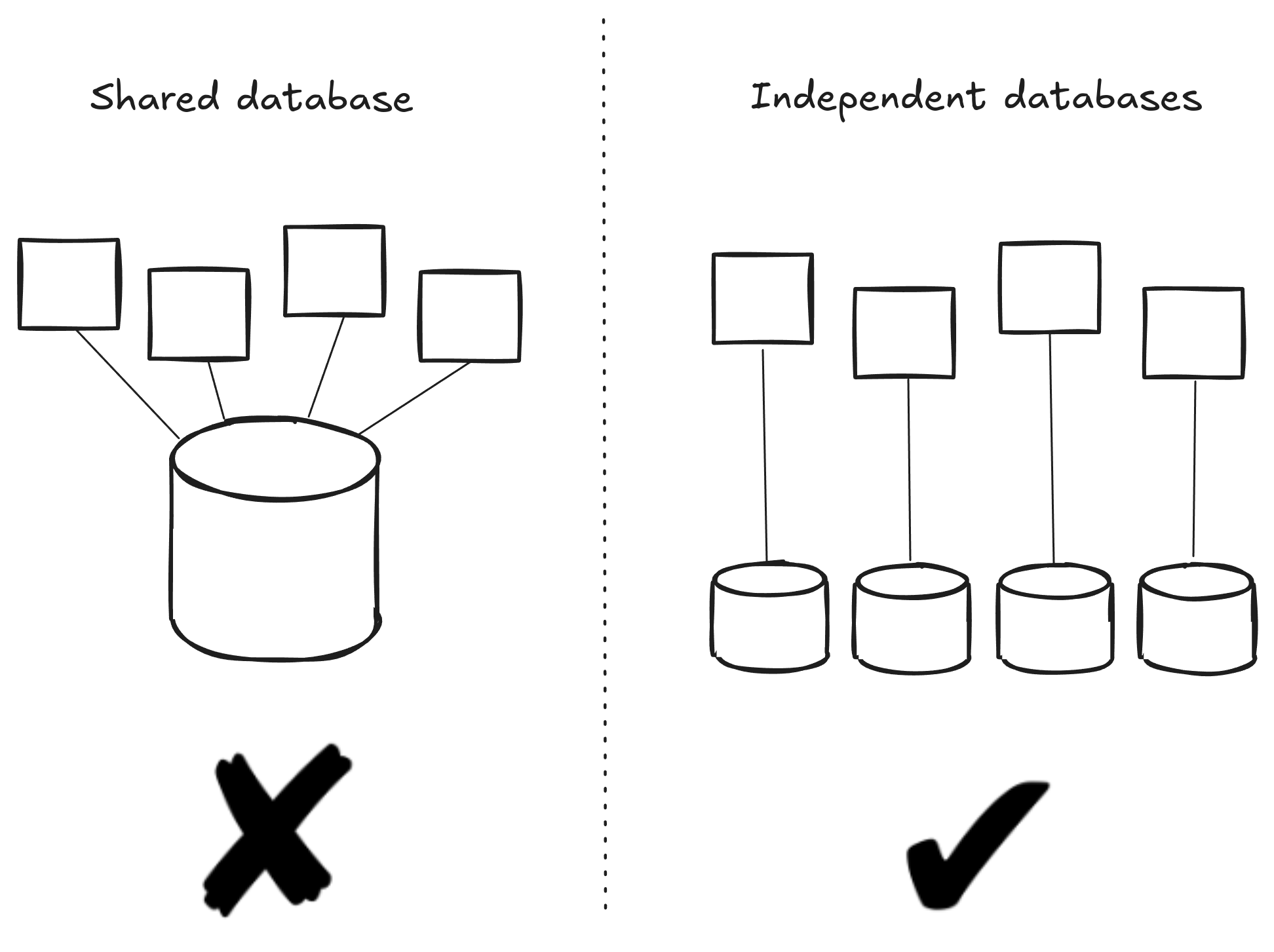

Use a shared database

If there is only one fixed rule of working with microservices it should be this: avoid using a shared database.

But maybe you missed the memo and now all your microservices use the same database.

Now you have no data encapsulation, high-coupling between services, a single point of failure and a scalability bottleneck.

Congratulations, you have circumvented many of the advantages of microservices.

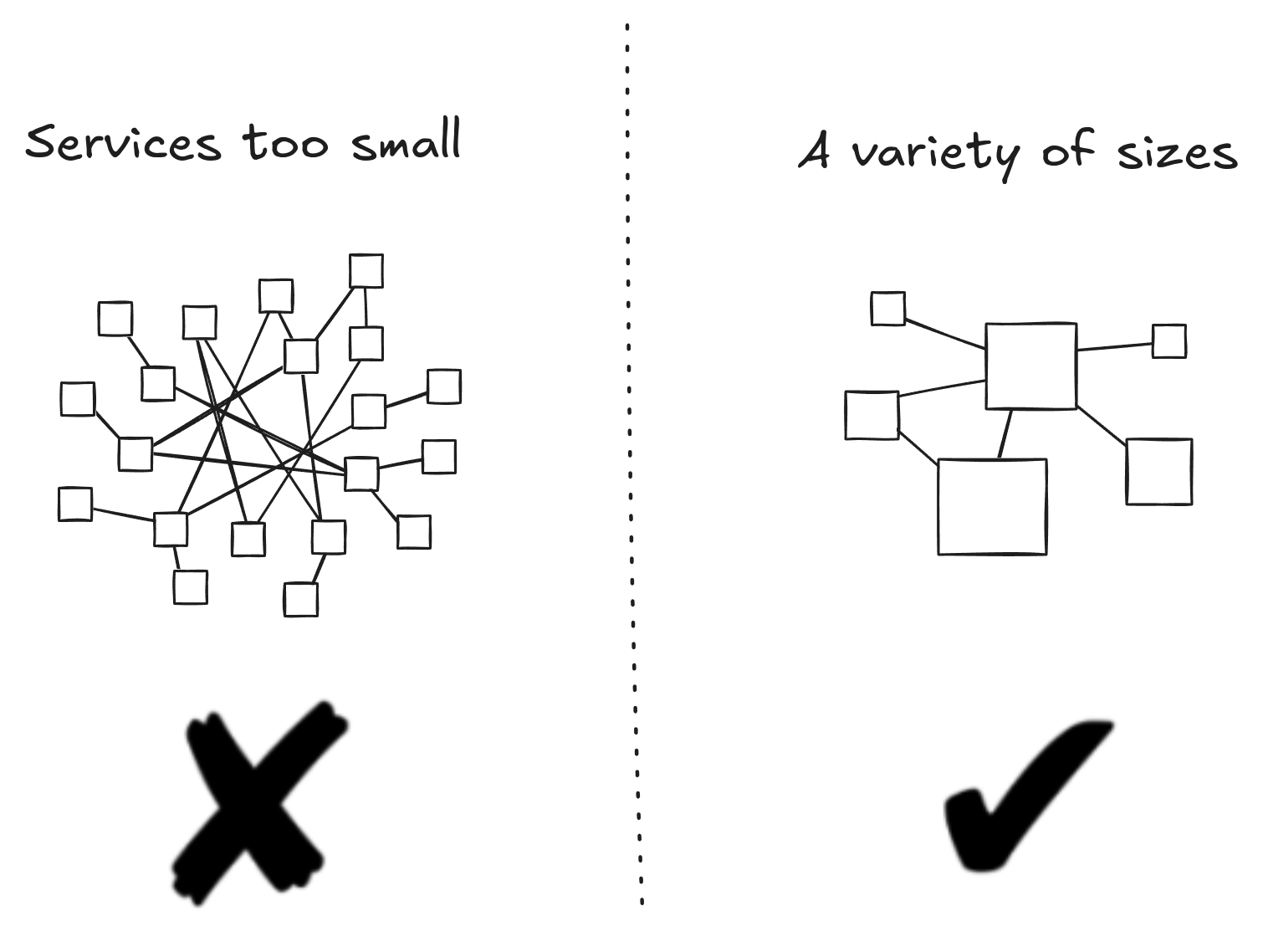

Make your microservices as small as possible

It’s microservices, so that means we are supposed to make them as small as possible right?

You might like to model your services on technical concerns (as opposed to business concerns). For example creating a microservice for each database query (I have actually seen it!).

You might have thought that a microservice-per-database-query was a good way to separate your data concerns, but then you remember that’s impossible because all your services are sharing a single database.

Basing microservices on technical concerns results in unnecessarily small services with a growing cost to maintain them. With smaller services you’ll need more of them to make it work - making the overall application more complex than it needs to be, because your services are smaller than they need to be. An increasing number of services creates an exponential increase in communication pathways and a much larger cost for network operations.

Microservices should be modeled on business needs and not on technical concerns. Each service should be the size the business needs to be and no smaller. Yes this will mean you will have a range of sizes for your services, but so what - no one cares how big or small your services are.

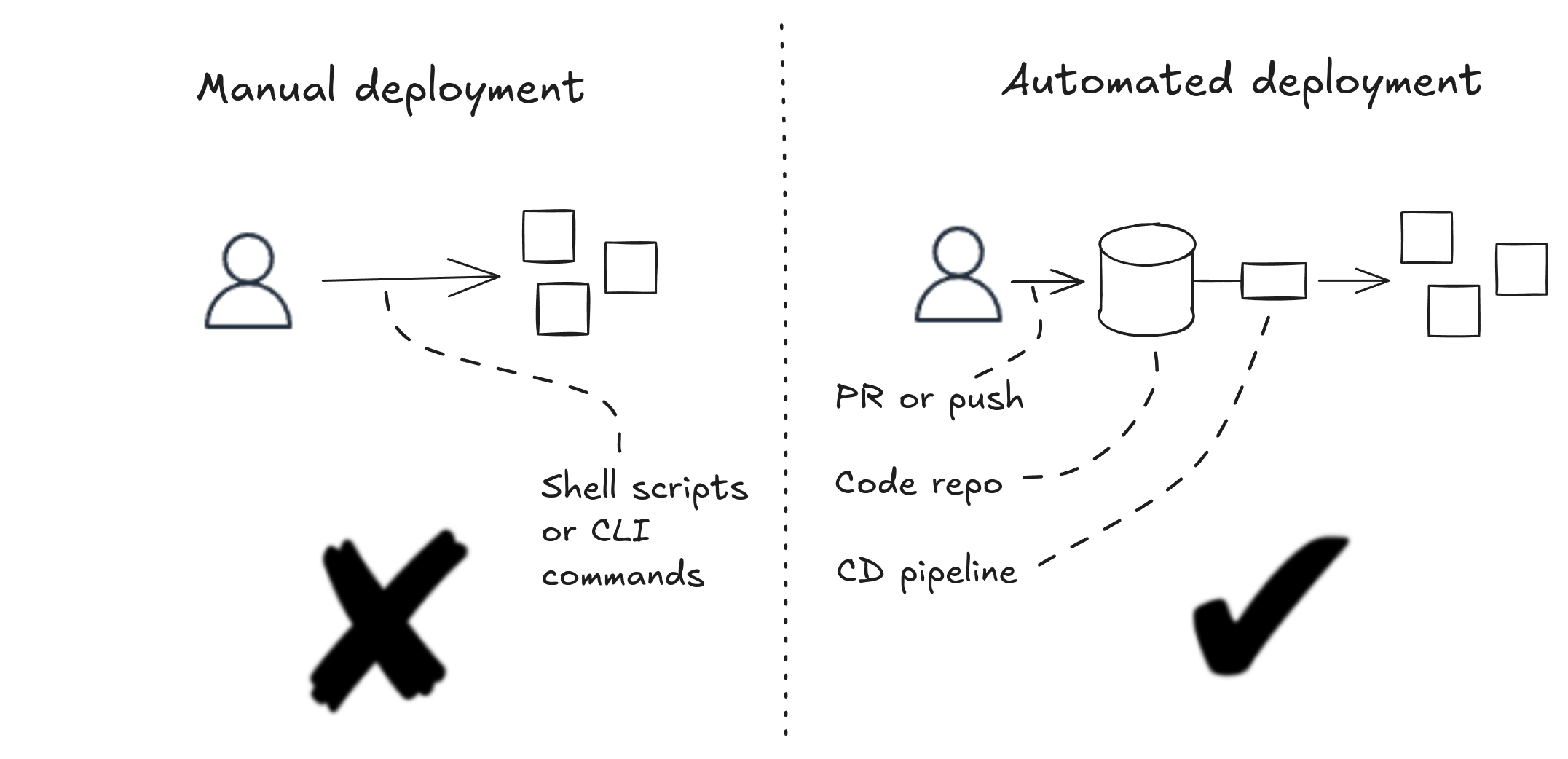

Use manual deployments

When someone new is starting to work on your established microservices application and you find yourself explaining to them the instructions for manually deploying each and every microservice, at this point you should definitely know that things are not going well.

But maybe you don’t realize the negative impact that error prone manual deployments can have on the development process. Your developers will be burning time on avoidable problems.

Automated deployments are one of those things we have to get right early, when there’s only a handful of microservices. If you wait until you have 100s of microservices, it becomes a more difficult problem to solve.

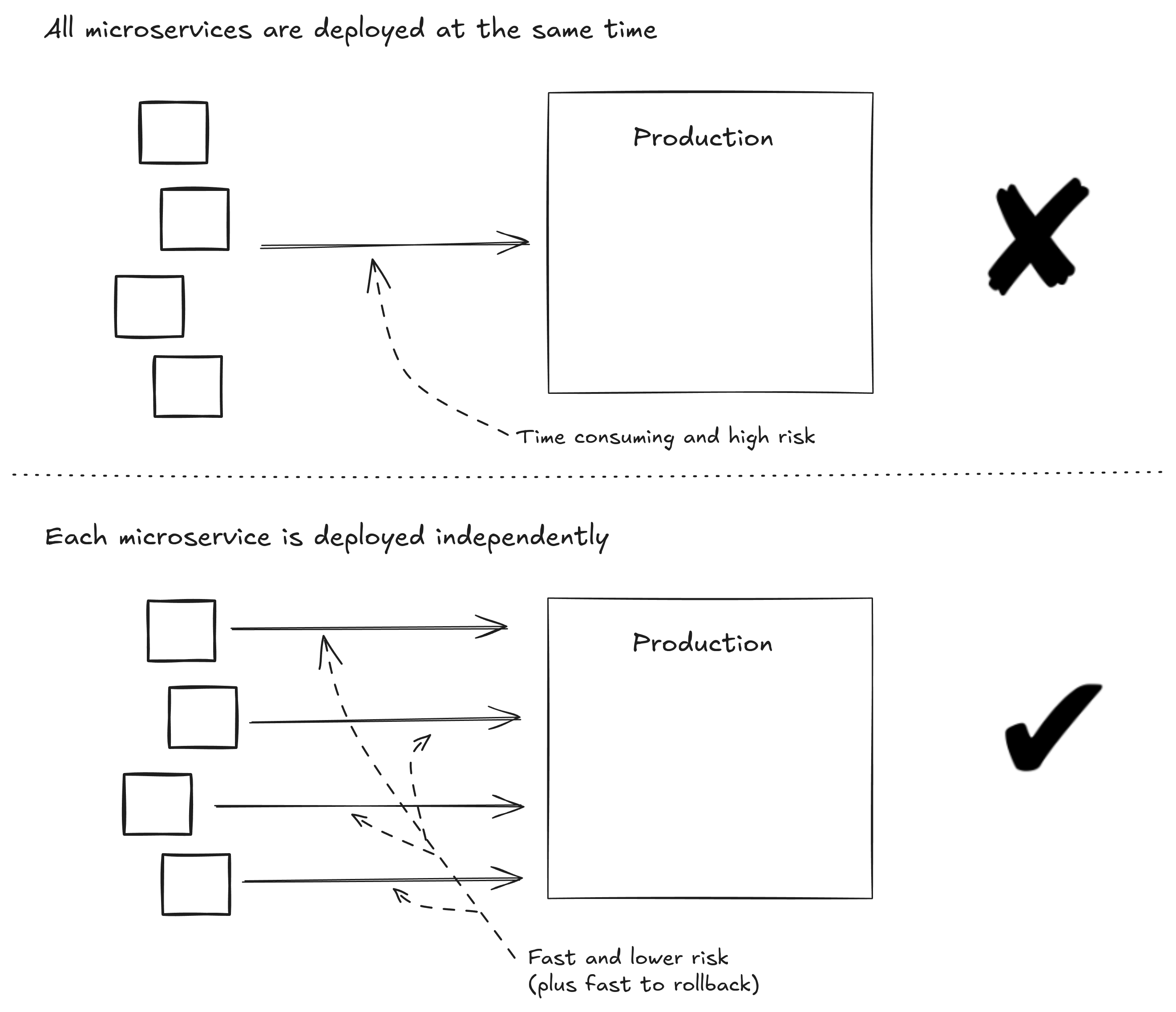

Deploy all microservices in lockstep

Feel like you need absolute control over the deployment of your microservices application? Prefer that deployment worked like it did when it was a monolith? Create a deployment pipeline (a manual one if possible) that deploys all microservices in lockstep, that is to say deploy them all at the same time in bulk.

Great work, now you have a distributed monolith. It’s kind of like the worst of both worlds and it destroys one of the most important benefits from microservices. When microservices can be deployed independently, as opposed to all at once, it decouples developers and teams, allowing them to release updates at their own pace without being deployed by the deployment process or other teams.

Independent microservice deployments are fast and they can also be rolled back quickly. Lockstep deployments on the other hand are slow, each one takes longer to test and deploy and it’s more difficult to rollback when things go wrong.

The time it takes to organize, test and actually deploy in lockstep decreases your ability for continuous deployment, but I’m guessing that the ability to respond quickly to customer demands isn’t a priority for you. I hope you have a great QA department. (But no one seems to have a QA department anymore).

Make it difficult to test

To really stunt the effectiveness of your development team, make it difficult for them to test their changes. Of course, this is an easy trap to fall into when working in a complex cloud environment, especially when there’s a pressure to skimp on testing to get things done.

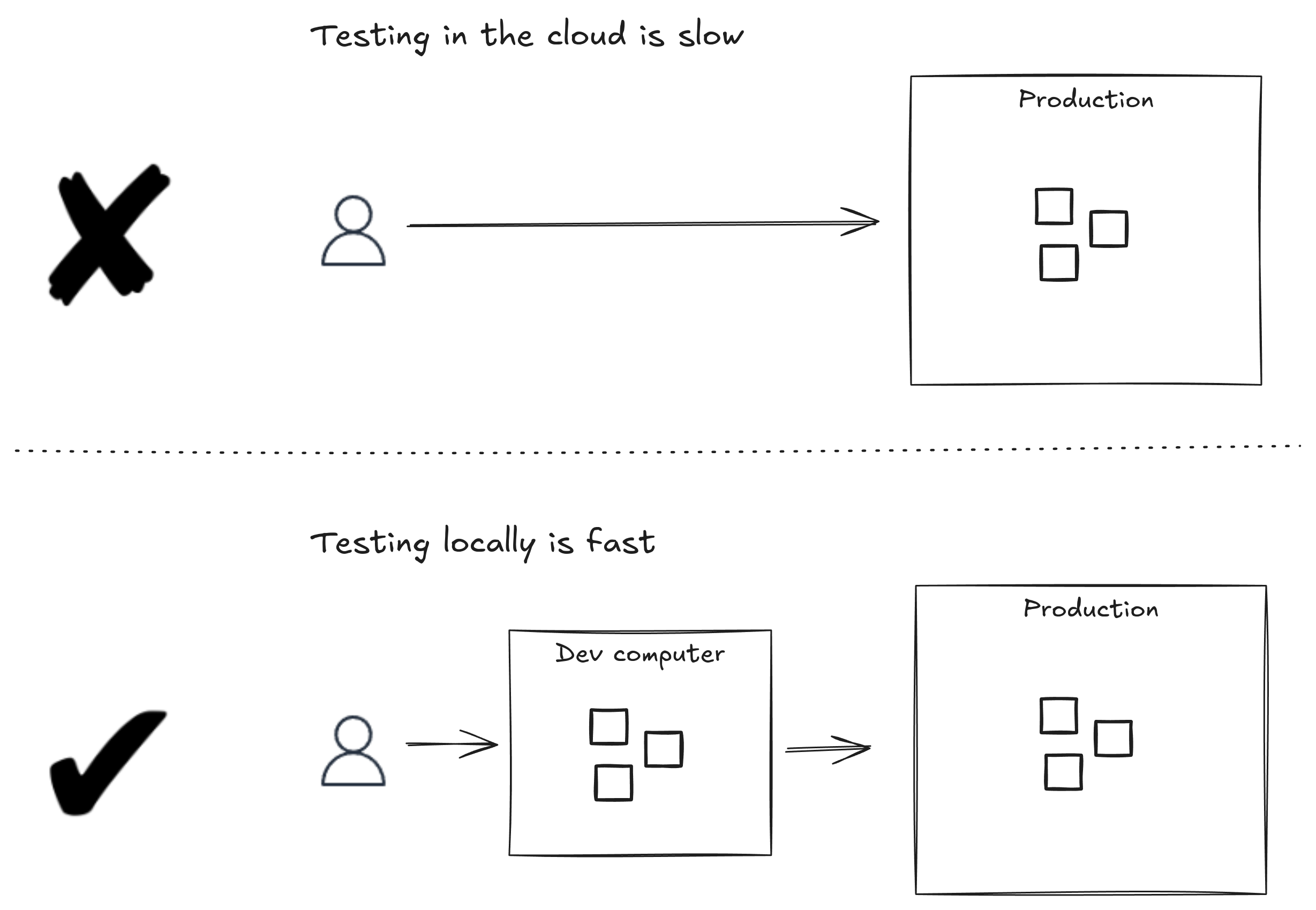

Reproducing complex configurations locally can be very difficult, so it’s easy to lose the ability to test locally and fall into the bad habit of having to deploy first before being able to test code changes.

Being able to test code changes locally is required for a fast development pace. When your developers are forced to test their code by deploying it (manually!) to dev, QA, test or staging environments they will be moving at a very slow pace.

With local testing, developers can make code changes and see results immediately, resulting in fast feedback and allowing for rapid experimentation to quickly test new ideas and find fixes for problems. Developers who are testing their code in a cloud environment must go through the whole deployment process even for just the smallest experimental code change. In the cloud (when running on someone else’s computer rather than their own local development computer) it will also be significantly harder to debug any problems in the code, not to mention problems caused by your manual deployment process.

Local testing is important for a fast development pace, but it’s not enough. Developers also need access to a realistic production-like testing environment. Ideally they should be able to reproduce problems from customer bug reports in the same environment as the customer. If that’s not possible for security or privacy reasons, they need systems and infrastructure that allows them to reproduce the production environment as closely as possible (minus any private or personal customer information) and as quickly as possible.

If your developers can’t easily reproduce customer problems there is going to be a massive disconnect between the problems hurting customers and the problems the developers are chasing. If developers can’t precisely and reliably see the actual problems customers are having they will burn time hunting the wrong problems.

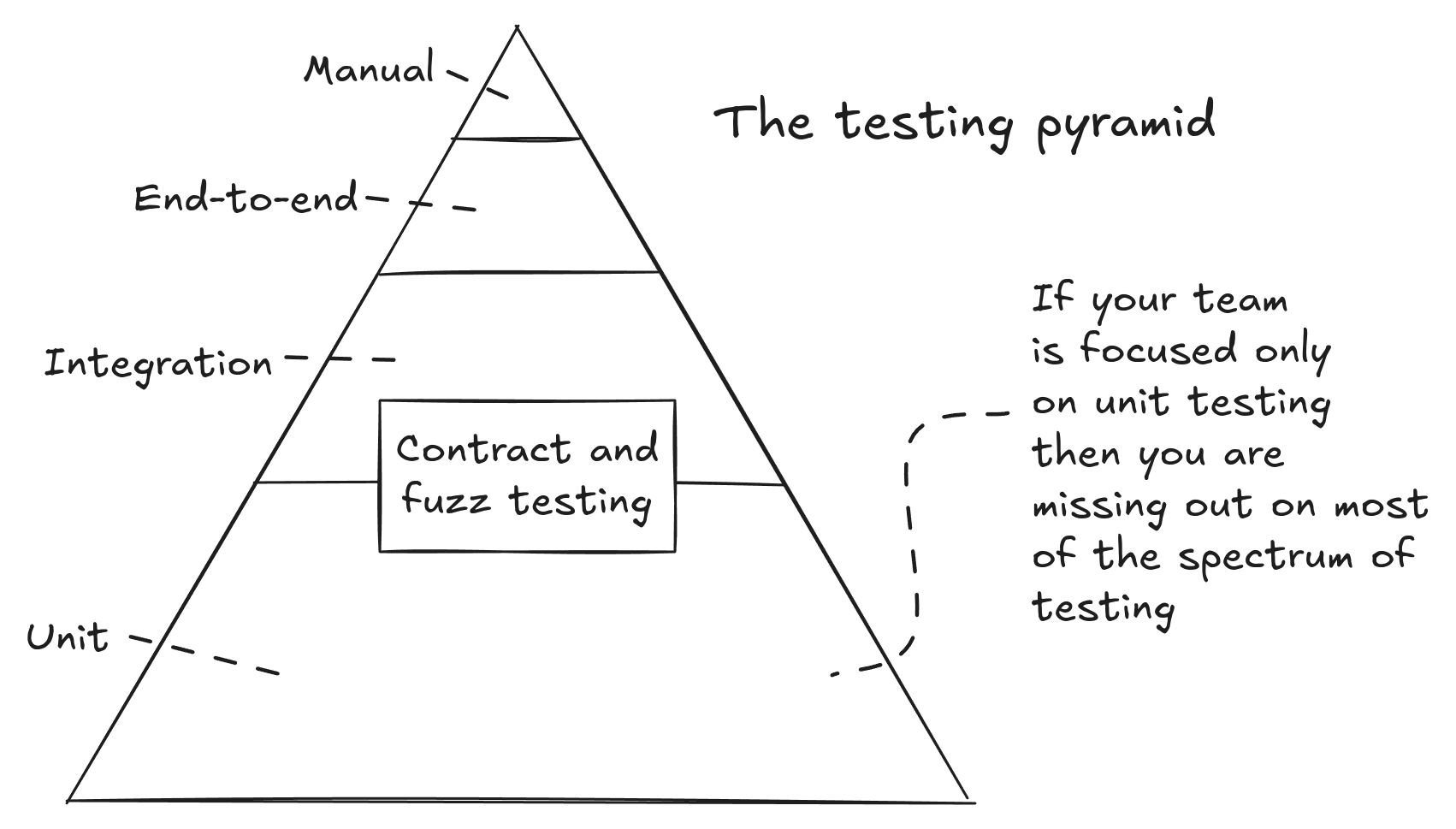

Focus only on unit testing

Some teams only seem to know about unit testing, which seems weird to me. Don’t they know there’s a whole spectrum of testing techniques?

If a hammer is your only tool, then every problem looks like a nail. If all you know is unit testing, then you are going to end up debugging lots of problems that are otherwise preventable if only you were using a selection of testing techniques across the testing spectrum from unit testing up to end-to-end and manual testing.

Also unit tests, although quick to run, are the most time consuming tests to write and maintain. I believe that unit tests should be reserved for business logic. But that implies extracting your business logic from all the technical and presentation concerns - something you probably aren’t doing, meaning that if you want to unit test anything, you are probably trying to unit test everything, even the code that really doesn’t deserve to be unit tested.

When you force your developers to burn all their time on unit tests they simply won’t have the time to explore more time efficient forms of testing. Good use of integration tests, end-to-end tests, contract tests and snapshot/output testing gives a lot of coverage for much less effort.

Manual testing also still has an important place and I would say you should not even be attempting to use automated testing when you don’t even have a manual test plan for your product. It’s so cheap and easy to invest in a manual test plan that everyone can use, it’s much cheaper than automated testing and personally I still believe it’s necessary even after you are successful across the spectrum of automated testing.

Have inadequate tooling

Any microservice application needs a lot of tooling. We need tooling for builds, deployments, managing services and infrastructure, testing, debugging and observability. If you are lacking sufficient tooling in these areas it's going to cause a massive, but difficult to see, drain on your development team who will be stumbling about in the dark just trying to understand what is happening, let alone how to fix problems.

Sometimes we need to build tooling as well when it doesn't already exist. Fortunately big companies have mostly already done this for us and there is plenty of good tooling out there (Postman and Backstage come to mind). But when big companies haven’t provided for us, or if we are a big company, or if we are just trying to do something different or unique where some custom tooling would really help… we need the skills and the motivation to build that tooling ourselves (and if we are nice, release it as open source for others to benefit).

Have inadequate skills

In addition to adequate tooling, we also need adequate skills in using our tools, practicing development and designing distributed applications.

Success with microservices really needs a culture that is striving for technical excellence and practicing continuous improvement. If you don’t have that, you might struggle to get developers to the level of proficiency demanded by distributed applications.

Make everything as complex as possible

When you make everything as complex as possible (the architecture, the code, the development process) you impose a cognitive tax on your developers that causes them to burn unnecessary time on chores and busy work.

Have as many small services as you can, so that any given coding task must necessarily be spread out over a number of services. Make sure the code in each service is spread out as well, so that even making the smallest change requires following a web of interactions across files. Use broken and leaky abstractions so that any advantages from those abstractions are overwhelmed by the complexity they add.

When you have an unnecessarily complex process, your development team will engage in a kind of process theater, where successfully navigating the complicated rules of the process trumps delivering value for the customer and the business. If your developers are constantly busy, but producing little in the way of real value, maybe it’s time to reevaluate how your process is actually working out.

Hopefully it’s obvious that I’d prefer things to be simple. Any modern application is going to tend towards complexity, but that doesn’t mean we can’t strive towards simplicity where possible. We should actively manage complexity, dividing it up into simpler parts and using good abstractions when that makes things simpler.

Believe it or not, microservices are intended as a way to manage complexity. Used well, microservices don’t cause extra complexity, they help deal with the complexity that was going to be there anyway. But use microservices badly and your problems will be compounded.

Don’t write anything down

According to The Agile Manifesto, working code is generally preferred over documentation. Isn’t this just a great excuse not to write documentation?

When an application gets really complex, when no single person knows how it all works or when it’s difficult to understand how to test it, or even just when you want new starters to have a good time, documentation can be really valuable. But only if it’s consistent.

Without documentation developers who are new to an application or a particular microservice (or haven’t been in those parts for a few months) must reverse engineer the code to understand how to update and test it. It’s not effective to have your developers doing this time after time. Any developer who routinely creates or updates documentation helps future developers (and their future selves) get up and running more quickly each time they return to a subsystem or service.

You won’t be successful with documentation until it becomes an important and valued part of your culture.

Don’t have a plan for the future

Ultimately the best way to ensure the devolution of your application to a distributed ball of mud is to have no viable plan for the future.

Don’t have a strategy for development. Don't have a vision for the architecture. Don’t have a plan for managing technical debt. Certainly don’t communicate the plan to the team. Definitely don’t take feedback from the team on what’s wrong with the architecture, the code and the development process.

Of course the extreme opposite of not having a plan can be just as bad. A micromanaging control-freak of an architect can be disastrous in other ways.

What’s needed is something in between. A strong architectural vision, but constantly adapted to reality and taking new inputs from the world. One that gives the developers the scope they need to make decisions and solve day-to-day problems whilst making consistent progress.

Do we really need microservices?

Have I convinced you not to use microservices? Looking at the list of ways to fail at microservices (a reminder, I have seen all these failures in the wild in recent times), you might wonder why anyone would even consider using microservices at all.

This is a valid point. Microservices are going to cost a lot. Before adopting them we must be able to articulate a good justification for them. If we can’t show how the benefits outweigh the costs, then we have no business using microservices. We also need a team with the skills, tooling and architectural knowledge that microservices demands.

With that said, there are many benefits to be had from microservices and valid use cases for them. And there are companies already using microservices and failing in some big ways. Using a monolith might not be appropriate. Converting from microservices back to a monolight might be infeasible. What else can we do?

Escaping microservices hell

If we are suffering from any or all of the above failures, well there is hope. There are concrete ways we can address these problems.

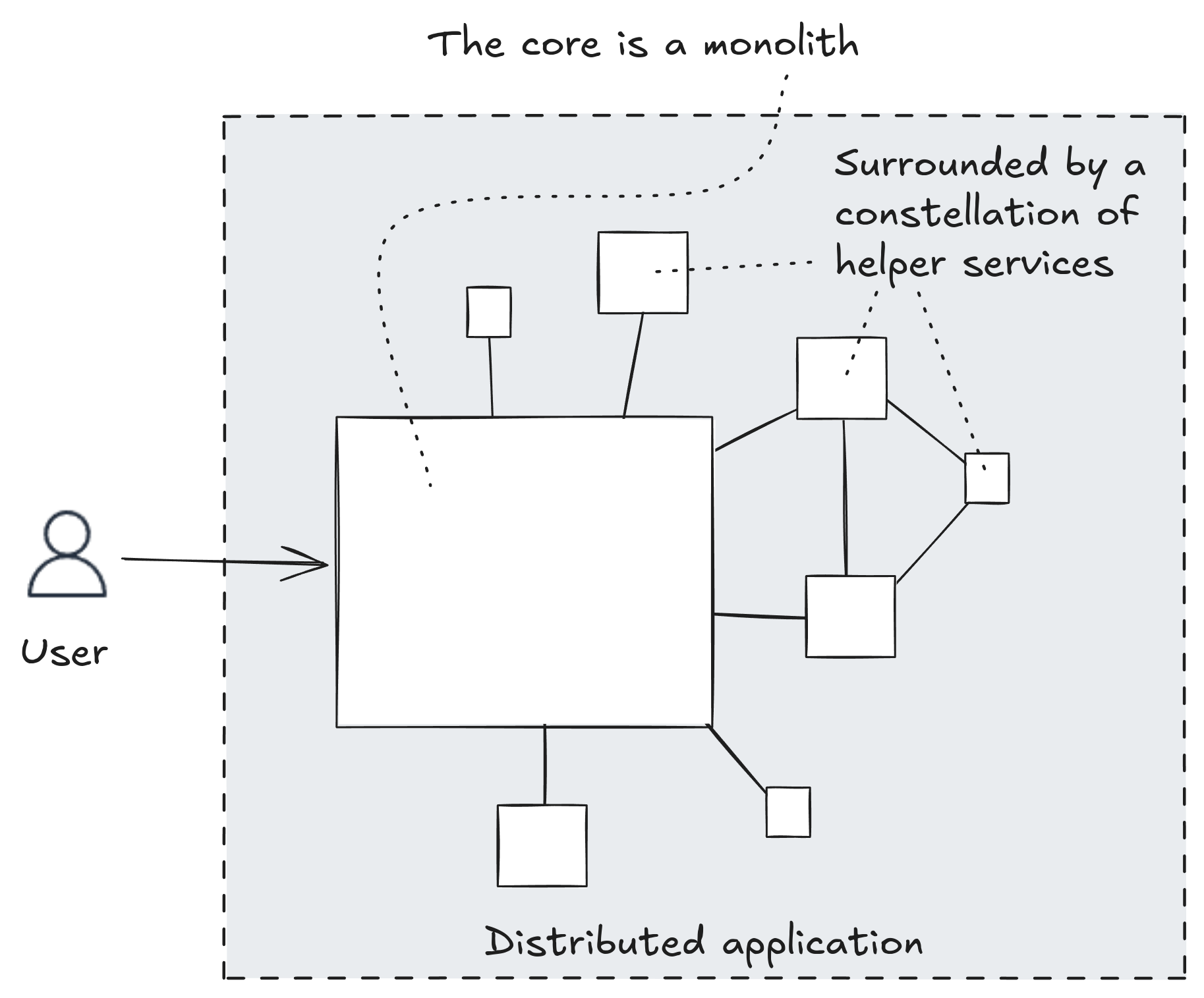

The first thing to understand is that it’s not all or nothing. It’s not just a case of microservices vs monolith, there’s a spectrum of choice between these extremes and positioning ourselves somewhere in the middle can give us the best of both microservices and monoliths.

The second thing to note is that nothing will change unless it is supported from an appropriate level in the organization. Sometimes that means you need to convince your fellow developers of the need for change, but more likely you need to convince the architects and the managers that there is a problem (or many problems as the case may be). If the higher ups don’t recognise the problems the team is facing or don’t understand the need for change, most likely your drive for change will get you into trouble rather than helping the team.

That said, here are the ways to tackle the failures mentioned above:

- Actively work on improving the developer experience for the team. Streamline and automate the development process where possible. Give your developers as much autonomy as possible. Listen to their feedback and give them permission to fix the problems that are in their power to fix. Happy, efficient, effective and invested developers are the key to many of the improvements we need to make.

- Fix problems early if you can. Don’t wait until you have already built 100s of microservices. But if not, you have to reserve time every day for making progress on improving the following areas: deployability, testability, debuggability and observability.

- Model your software based on business needs and customer problems, don’t model your software based on technical concerns. Whatever state it’s in now… for any changes or additions, model them in the right way before you make the change.

- Don’t make your services too small. Use modeling to figure out an appropriate size rather than trying to make them as small as possible. Consider merging related services that feel too small or don’t pull enough weight by themselves.

- Automated deployment must be fully automatic and extremely reliable, if not this is the first thing you should fix so as not to have the team spinning their wheels on avoidable deployment issues.

- Automated testing is very important for scaling the development of many services and I’m not just talking about unit testing. Learn every testing technique you can and make sure the team is using the most effective suite of testing they can. Build your own testing tools for unique use cases, but only when the value delivered outweighs the cost of building it.

- Rebuild your capability for local testing. If your developers can only reproduce the software in the cloud for testing you are in serious trouble. Invest whatever time is necessary for your developers to reliably test their code changes and additions on their local computer before they commit the code. If the system itself is too big to reproduce for local testing, you must find ways to reproduce parts of the system while mocking or simulating the rest.

- Whether or not you are good at testing, debugging problems and figuring out how to fix them is going to consume a huge amount of developer time. If you aren’t actively improving the debugability and observability of your application it’s probably going to be heading in the wrong direction. Buy or build the tools you need. Give your developers access to production or production-like environments. Find ways to make it easy for your developers to reproduce customer problems to give the developers the best possible chance they are hunting the right problems.

- Don’t be afraid of documentation. Review and reward documentation with the same level of attention and appreciation as you do for code. Foster a culture of sharing knowledge. Realize that documentation isn’t just writing things down in a wiki, it can come in a variety of formats:

- Good descriptions and readmes for each repo.

- Readable code and code samples.

- Test cases and test plans.

- Architecture decision records.

- Detailed annotated diagrams.

- Internal blog posts.

- Recording videos for the team to watch later.

- Work towards a culture of technical excellence and continuous improvement. Being successful with microservices requires the use of many (wonderful) tools and we need a team with high levels of skill in all facets of distributed applications development.

- Actively simplify your application by continuously striving to remove complexity that doesn’t pay for itself. Work constantly to reduce or remove unnecessarily complex code, architecture or processes. This reduces the cognitive tax on the developers in their day-to-day work: you want them solving customer problems, not problems coming from unnecessary complexity. Refactoring (supported by strong testing) should be a daily ritual part for each developer. If they aren’t doing this you aren’t heading towards a simpler and more manageable system. Instead you are heading to an ever more complex and unmanageable system.

Ultimately we have to ask ourselves the following question: Do microservices make it easier for our developers to safely and reliably get useful and valuable features and fixes into production?

The purpose of a microservices architecture is to reduce deployment risk. It works by dividing up our deployments into small parcels. Because each parcel is small it is easier to understand, easier to test and easier to deploy independently. It’s also easier to rollback when things go wrong.

If instead microservices make deployment more difficult for you, it means you are probably using them the wrong way and maybe you are making some or all of the mistakes I have outlined. If you are unwilling to make the investment required to get microservices right, maybe the right choice for you is to use a monolith. If that’s not feasible, instead consider using a hybrid model with a variety of service sizes from monolith to microservices, depending on your needs.

The most important way to ensure success

If you don’t have a strong vision or plan for your application, it could mean you are heading in the wrong direction. Or worse: that each developer has their own separate direction.

Any plan you have must be updated continuously, to keep it adapted to the unfolding reality. Involve the team in creating and updating the plan, that’s the best way for everyone to become invested in it. Communicate the plan to stakeholders and make sure management understands the reasons why it is important.

Everyone has to be onboard. There has to be someone who champions the vision for the architecture and brings everyone into agreement on it. It’s not enough just to document the existing architecture, there needs to be a plan for the future and it needs to be spearheaded by someone who isn’t afraid to get into the nuts and bolts of the system and understand the details of how it works. Bigger-picture knowledge is built from lower-level knowledge.